Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

When Julia Fox recently posted her apartment tour on TikTok, what was most surprising to everyone was how not aspirational it was. The fashion world darling, who’d previously been seen double-fisting Birkin bags, was suddenly talking about her humble-by-celebrity- standards digs and persistent mouse problem. And for the most part, people loved it.

Fox is one of very few influencers to be lauded for her down-to-earth behavior recently. With “Lashgate” and elaborate influencer trips in the news, her cohort tends to make headlines for being the opposite of relatable. Pop culture is increasingly suffused with an “eat the rich” mentality (look at The White Lotus, Glass Onion, Triangle of Sadness, or The Menu, for example). Amid economic turmoil, inflation, and layoffs, the idea of the influencer-as-aspirational goddess is plummeting down to earth.

Elaborate haul videos, ostentatious unboxings, and an endless crawl of consumption, once synonymous with influencer culture, have become déclassé. Many in the fashion space had dialed things back in the name of sustainability. Now, even more are doing so in the name of relatability. Hence the burgeoning “de-influencing” trend, in which people tell you what products they don’t like. Even the so-called “corporate girlie” genre of TikTokers, who would chronicle their latte- and nap room-filled existence as tech employees, have been pivoting to posting about labor rights, according to a recent NBC News story.

Ever since fashion bloggers made it to the front row at a D&G show in 2009, there have been predictions about the end of influencers, their privileged bubble deflating with a decisive pop. But as austerity reigns, it seems that what’s coming isn’t the end, but an evolution that will cull those who don’t adapt accordingly. The challenge, of course, is for the influencer, whose job is predicated on aspiration, to square the circle of being relatable—just not so relatable that she becomes that dreaded thing: boring.

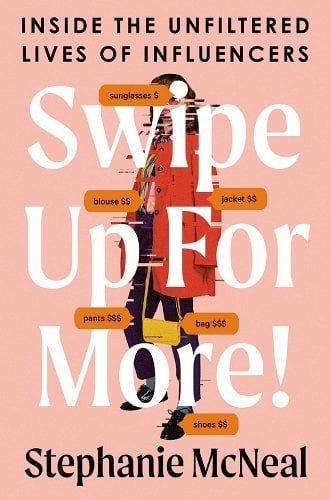

Stephanie McNeal, a senior culture and features reporter at BuzzFeed News who covers influencers, has a book on the topic, Swipe Up for More!: Inside the Unfiltered Lives of Influencers, coming out in June. One of the women she profiles in its pages, she says, has found that “as soon as she shows any part of her life that isn’t super relatable, her followers turn on her.” Part of the problem, McNeal says, is that “people still refuse to believe that being an influencer is work. There are people who are doing the exact same thing for companies,” namely content creation, “and that’s considered a real job. But if you’re doing it for yourself, it’s not considered worthy of the same level of respect.”

Since about 80 percent of influencers are women, she believes sexism plays a significant part. “If this multi-billion-dollar industry had been created by men, the reception would be different…It’s not just the fact that these are women doing it, but that they’re engaged in traditionally female pursuits, whether that’s makeup, or beauty, or fashion, or parenthood…things that are considered not work.”

Says Kirbie Johnson, a beauty reporter and co-host of the beauty podcast Gloss Angeles, “Young women are always going to be exploited, but also discussed in a negative light. So, I think people are lashing out in hopes that influencers will die out, but that’s not going to happen.” McNeal adds that they can be an easy target. “When we do experience these times of economic downturn, I think people will probably turn on influencers first, because they’re really accessible and easy to throw tomatoes at, as opposed to yelling at, I don’t know, J.P. Morgan.”

Johnson thinks the platforms themselves are also driving this shift. TikTok initially drew people because it promised that “anybody could be an influencer,” she says. She points to a 50-something woman who went viral for posting about a Peter Thomas Roth de-puffing under-eye serum. “This woman was not a content creator; this was not her full-time job. She just wanted to share the gospel of this product, and sold it out. And I mean, sold it out to the point that PR didn’t even have it available for editors who wanted to try it for themselves.”

Back then, TikTok felt refreshingly ordinary; these days, of course, the platform is minting its own megastars, who come complete with their own #spon. This new normal has created a weird disconnect where some people are influencing—hard—while others are committed to de-influencing. Johnson says that when she goes on her FYP, “I feel like everything I see is someone trying to sell me something or tell me something sucks.” The takedowns help drive eyeballs, of course, but as a beauty professional, she doesn’t always find them to be helpful. “Everyone wants to hate the Dyson Airwrap because of how expensive it is. They want to poke holes in everything that could be wrong with it, and how there’s a better product that’s a fourth of the price. And as a beauty expert, I have yet to find a product that is as technologically advanced that doesn’t destroy my hair.”

McNeal predicts we’ll see more people “not trying to be everything for everyone. There are a lot of influencers who have started to say, ‘Look, I don’t want to have a million followers. I’m not trying to make Reels every day to go viral. I’m kind of good.’ And these are people, in general, who have been in the game for a really long time. They might have 100,000 followers, but they have very loyal followers, people who are like, ‘I’ve been following this person for 15 years, and when she posts a jacket, I’m going to buy it, because I really trust her.’”

“If you’re not a fan of influencers, you’re going to have to figure out a way to deal with it, because they’re not going away,” says Johnson. She does think certain figures will weather the turbulence better than others however—like Emma Chamberlain, who she says balances “aspirational and authentic and relatable really well. She hasn’t changed the brand of person that she is, but the opportunity that she’s been presented is aspirational, and people love that. That’s why they root for her.”

The Great Depression brought us escapist entertainment—with Carole Lombard and Kay Francis playing heiresses going on cruises and swanning around in silk gowns—which might be a sign that people don’t actually respond to unvarnished reality quite as well as they claim to, even in challenging times. Johnson makes an analogy to the scripted entertainment that came out during the height of the pandemic about COVID-era life and social distancing. “Nobody wants to watch that. I need something to take my mind off the fact that we can’t see our family and friends,” she says. “There are people on the platform that are very honest: ‘This is my life. This is not the most aspirational life to be living, but I’m doing it and I’m working hard.’ People do watch that, and they actually root for the person that’s trying to better their lives.”

But, she says, “it has to toe the line between being authentic and aspirational. You can’t just be like, ‘I woke up in my $5 million mansion, and then my nanny took my children. And then I spent three hours going to Pilates.’”

It’s Time for Influencers to Be Real

News Reports PH

0 Comments